Yesterday's People: going,

going, gone.

|

|

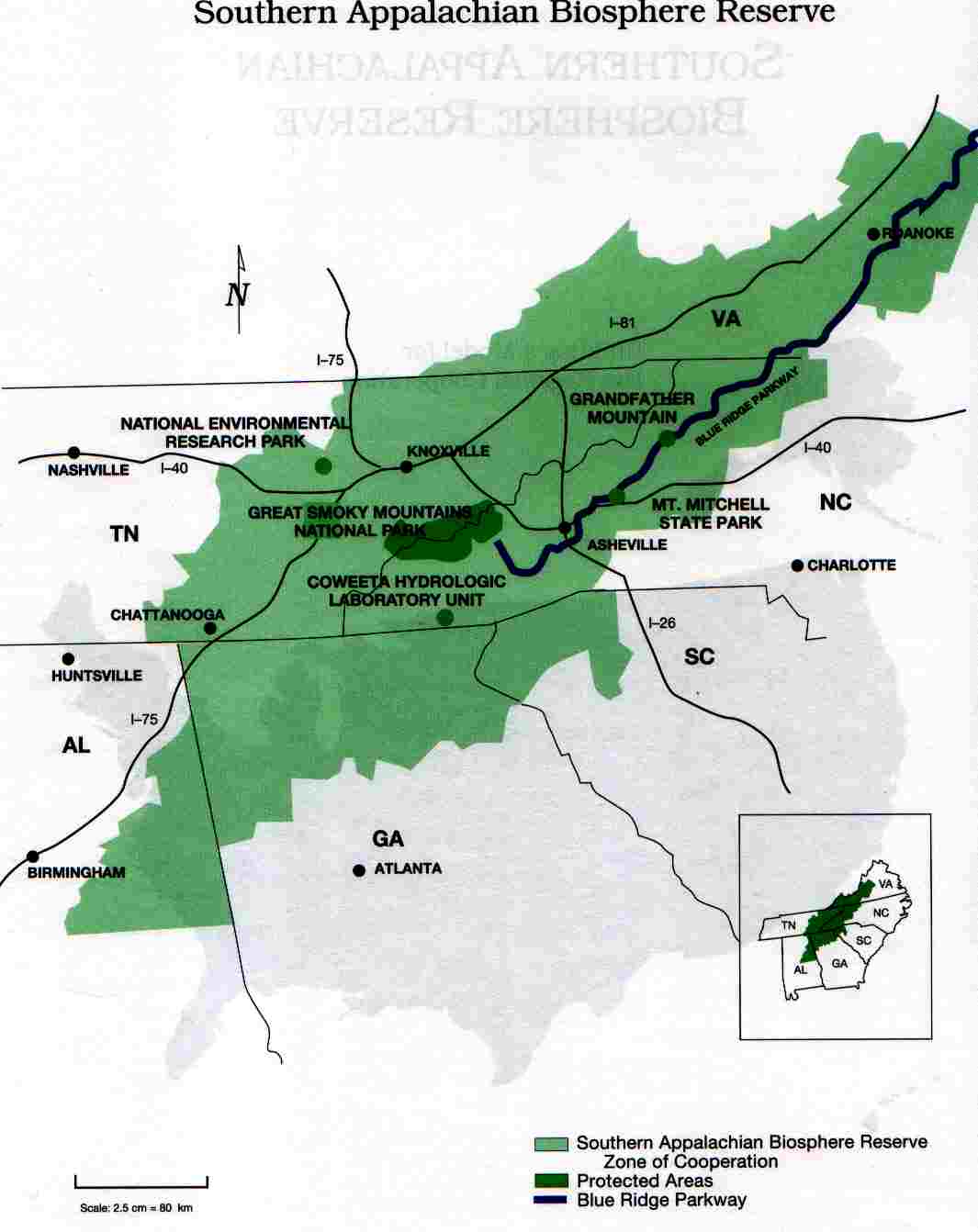

| This map taken from Biosphere Reserves in Action, published by the U.S. Man and the Biosphere Program, U.S. State Department, p. 66, The Southern Appalachian Biosphere Reserve is one of 47 such U.N. Biosphere Reserves in the United States. Not one has ever been approved by any elected officials. |

The requirement is not legally binding; there are no penalties for non-compliance, but by virtue of the United States agreement with UNECSO, we have agreed to "voluntarily" comply with the management dictates established by UNESCO. Consequently, the various government agencies that are responsible for meeting our national obligations to the international community, have been devising ways to achieve UNESCO's management objectives, using domestic law and regulatory powers.

The first principle of Biosphere Reserve Management, is to continually expand the core wilderness areas through restoration and rehabilitation of adjacent buffer zones, and to connect those core areas with "corridors" of wilderness. As the core wilderness areas grow, so too, must the adjacent buffer zones expand into the zone of cooperation. These zones of cooperation are the areas surrounding selected communities that are being transformed into "sustainable communities," to accommodate the people who are displaced by the expanding wilderness areas and connecting corridors.

Much to the chagrin of the wilderness planners, there are both yesterday's people, and many more of today's people who now live in areas that the planners covet. In Cuba, or in many of the countries of South America or Africa, government could, and has, simply ordered the people out.

Not in America; government has to be much more subtle, even devious.

The Conasauga River in Eastern Tennessee flows through one of the most coveted areas to be "restored." Not many, but several families and businesses inhabit the area, mostly dependent upon logging for their income. The government did not issue a relocation decree, they issued instead, a new water standard for the Conasauga River. Already one of the cleanest streams in the entire United States, the EPA requested the State of Tennessee to elevate the purity standard to a level that would have virtually eliminated the possibility of disturbing the land anywhere near the river. The people who live there would have to move out, if the regulation - created by appointed bureaucrats - were implemented. This regulation is still pending as the result of local landowner opposition.

The Upper Catawba River Basin in North Carolina is another area coveted by the wilderness planners. Both of these areas were targeted on 1992 maps produced by the Wildlands Project. Until now, the few people who lived in the Catawba River Basin who even knew of the Wildlands Project, paid little attention. Now, their attention is riveted on a new regulation being proposed by the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission which could force the removal of scores of families, and financially devastate those who choose to remain.

The proposed rule would create a buffer zone - 50-feet wide - on either side of every stream. This may not be a problem in Arizona, where there may be one stream every 50 miles, but in the mountains of Western North Carolina, there is a steam pouring from every other rock. Several landowners in the area have analyzed the impact of the proposed rule on their private property only to learn that 50-percent, and more, of their land will no longer be usable for anything except for calculating the amount of their property tax.

The rule does provide an escape valve. If a person really, really wants to use his own land, that happens to be in a buffer zone, then they may pay a "mitigation fee," at the rate of $1.44 per square foot, in the outer 20 feet of the buffer zone, and $1.92 in the inner 30 feet of the buffer zone. This could amount to a sum in excess of $75,000 per acre that a land owner must pay to use his own land.

Reasonable people might think that since the state will require a land owner to pay upwards of $75,000 per acre to use his own land, then, of course, the state should pay the land owner an equal sum for forcing him not to use his own land. But the state is not reasonable; there is no provision in the proposed rule to pay the land owner a dime for taking the use of his property for public purposes, even though the U.S. Constitution specifically requires government to do so.

No one in any state agency will admit that the proposed rule has anything to do the U.N. Biosphere Reserve, or the Wildlands Project. Can it be a coincidence that in 1992, the Wildlands Project published a map of the Southern Appalachian Biosphere Reserve, in which the North Fork Catawba River is identified as a "proposed corridor," linking two "proposed core wilderness" areas on either side?

|

| These maps taken from Wild Earth, Special Edition, 1992, p. 55. |

|

| Enlargement of the map above, showing clearly that the Catawba River Basin was targeted to be a buffer zone for two proposed core wilderness areas on either side. Core wilderness areas are off limits to human beings. |

Coincidence or not, the state is implementing the Wildlands Project regardless of what they call it. The Wildlands Project is "central" to the implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity - which was not ratified by the U.S. Senate.

Why is the State of North Carolina implementing the Wildlands Project? Because agencies of the federal government are insisting on the implementation of policies with which the state is required to comply in exchange for federal dollars. Why is the federal government implementing policies contrived by the IUCN and UNESCO under the guise of "Ecosystem Management?"

Ask Al Gore, who, with President Clinton's blessing, transformed the EPA, the Department of Interior, and the Department of Agriculture to implement policies designed to achieve international objectives - with or without Congressional approval.

The ultimate objective is to remove as many rural residents as possible, eventually all of them. Western North Carolina is to be a model for the transformation of the entire United States, according to a 1992 Sierra Club proposal, into 21 bioregions across North America.

Western North Carolina is no longer safe for yesterday's people, or for the newcomers, if they live outside the cities and towns that are being transformed into sustainable communities. Rural people, wherever they live, are going, going, and soon - if the present policy persists - they will be gone.

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, any copyrighted work in this message is distributed under fair use without profit or payment for non-profit research and educational purposes only. [Ref. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml]