|

The taxes you pay: Lid on property taxes is tightening By

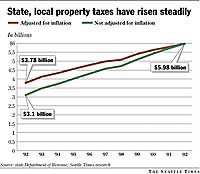

Drew DeSilver 12/12/02 When voters approved tax-limiting measures in 1997 and again in 2001, property values were soaring, especially in the Puget Sound area, and taxes were rising even faster. Today, property values are still growing, but tax growth is limited unless voters give the OK. In fact, the tax limits almost guarantee that property taxes will bear less and less relationship to property values as years go on. As a result, local governments that used to rely on rising property values to fund themselves will have to start looking elsewhere. Washingtonians can appear contradictory about property taxes. We dislike them in the abstract (51 percent of people in a statewide Seattle Times poll called the property tax unfair), and we vote to limit them for general purposes. But more often than not, we vote to raise them for specific, local purposes. A Seattle Times spot check of 2002 levy measures in most counties found that more than two-thirds passed. King County voters approved a record number of tax proposals this year: 46 of 60 submitted. Frustration surrounding the property tax is due in part to its opaque nature. Here's an attempt to shine a bit of light into the black box. I get my property-tax bill each February, and I don't understand what all those line items represent. One of the most important things to realize about the property tax is that it's really many taxes rolled into one big bill. In Washington, some 1,500 entities can collect property taxes. The state gets around $3 for every $1,000 in property value for K-12 schools. Next, the 39 counties each have a general fund and a road fund that can levy property taxes. (The road fund can only tax property in unincorporated areas.) Then come the 280 cities and towns, the 296 school districts, 400 or so fire districts, and hospitals, ports, parks, libraries and cemetery districts, and all the other special-purpose entities. King County, for example, has 39 cities or parts of cities, 20 school districts and 42 other specialized districts. It will get a 43rd next year because voters in the Finn Hill neighborhood north of Kirkland voted last month to create a new district to take over O.O. Denny Park. Why the complexity? Defenders of the profusion of local governments say it enhances local control because all those entities (except the state) must either adopt property taxes at an open meeting or go to their voters and ask for the money specifically. Critics, however, say the patchwork leads to misguided budgeting. "If libraries and parks are both provided by a county government, the county council can and should ask what mix of library and park spending would provide the greatest value to residents," said Kriss Sjoblom, chief economist at the Washington Research Council, a business-oriented think tank in Seattle. But, "when parks and libraries are provided by separate special-purpose districts, these trade-offs don't get explored. Each district just spends the taxes it is allocated for its own purpose." When my assessment goes up, so will my taxes, right? Perhaps, but not for the reason you think. Until recently, values and taxes tended to rise in tandem. But this was because taxing district officials had great freedom in deciding how much property-tax revenue to collect. State law limited the annual dollar increase to 6 percent. In areas

where property values were rising rapidly, districts could tap into

that rise — increasing the amount of money they collected while maintaining

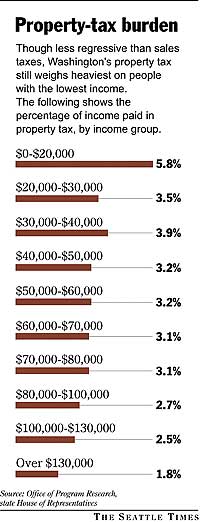

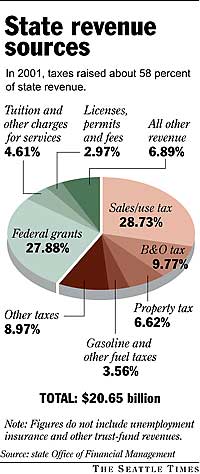

or even lowering the tax rates. The effect has been to start unhooking property taxes from property values. This year, for example, total assessed value in King County rose 12.2 percent, but tax collections were up just 5.2 percent. How does the county decide how much my property is worth? Each county's system differs. Some, like King County, revalue property every year, while others are on a two-, three- or four-year cycle. King County uses a rolling two-year database of sales in each neighborhood to determine how much comparable properties have changed in value. However, as Assessor Scott Noble readily admits, the system has a built-in lag: Taxes in 2003 will be based on property values set in 2002, which in turn are based on market information from 2000 and 2001. That's why assessed values are always somewhat behind market values. So what does property value have to do with taxes? Each taxing district, abiding by the restrictions in I-747, sets its budget for the next year and determines how much property tax to collect. The assessor takes that dollar figure, adds in any voter-approved levies, and divides the total into the total value of all property within that district. The result is a rate usually expressed as so much per $1,000 of value. The assessor repeats this process for each district within his county. Then the rates for all the districts your house happens to be in are applied to the house's assessed value. The result is the complex bill with big numbers and tiny type. Where are property taxes the highest and lowest? The overlapping of hundreds of taxing districts creates scores of different rates — King County alone has 265. But the average rate in each county gives a general sense of how things stand. This year, the highest average rate was in Garfield County: $15.83 per $1,000 of assessed value. The lowest: San Juan County, at $8.11 per $1,000. The biggest piece of the typical property tax bill is the local school tax. The Taholah School District in Grays Harbor County had the highest combined local rate this year, $8.83 per $1,000; Hood Canal in Mason County was lowest at 66 cents per $1,000. Eighteen districts levied no local taxes at all. Where have taxes and property values grown the most? Between 1992 and 2002, property values in little Wahkiakum County rose 161 percent; Kittitas, Pacific and Clark counties weren't far behind. King County, where total property value just about doubled, was slightly below the statewide average. In terms of taxes levied, fast-growing Clark County led the way with a 163 percent increase, followed by Wahkiakum and Asotin counties. King County, with an 81 percent increase over the 10-year period, ranked 28th; more than $2.3 billion was collected from county taxpayers this year. Who gets all that cash? Cities and counties split most of the rest: 17.8 percent for the counties, 13.9 percent for the cities. The remaining dollars were shared by fire districts, libraries, ports, hospitals and other public entities. Who pays the property tax? Individuals in Washington pay about 58 percent of all property taxes; businesses, which own a lot of property in the form of office buildings, shopping malls and factories, pay 42 percent. Businesses also are the main payers of tax on personal property — mostly machinery and equipment, as distinguished from real estate. An analysis by the state found that property taxes are regressive: They take a greater share of poorer people's incomes (5.8 percent for the lowest-income group) than of the well-to-do (1.8 percent for the highest-income group). (Along with taxes paid directly by property owners or as part of mortgage payments, the analysis assumed that property taxes are included in the rent that tenants pay.) What's been the impact of Initiative 747 and Referendum 47? So far at least, the tax-limitation measures have, in fact, limited taxes. A survey by the Washington Policy Center, a conservative think tank in Seattle, found that 20 of the state's 39 counties increased the dollar amount of their regular property-tax levies this year by exactly 1 percent; 12 held their levies even, while two raised them less than 1 percent. Only five increased their levies more than I-747's 1 percent limit.

I thought I-747 limited the annual increase to 1 percent. How can any cities or counties go beyond that? Through the miracle of "banked levy capacity." State law allows cities, counties and other taxing districts that raise their regular property-tax collections by less than the maximum to "bank" the unused taxing authority for future use. Since Initiative 695, which cut many local revenues by repealing the state car-tab tax, and especially since I-747, many districts have been drawing on their banked capacity to raise tax collections by more than 1 percent. The Port of Seattle, for example, used much of its $30.9 million in banked capacity to raise its 2003 tax revenues by $18.2 million, or 45 percent. Once used, however, banked capacity becomes subject to the I-747 limits. As the bank vaults are emptied, Paul Guppy of the Washington Policy Center said, more and more districts will be forced to stay within 1 percent. Any other impacts we should be aware of? Noble, the King County assessor, expects that property taxes increasingly will be determined at the ballot box, rather than by city councils, hospital boards or other governing bodies. In particular, Noble expects to see an increase in "lid lifts" — temporary increases above the 1 percent limit. Lid lifts have to be approved by voters, but they require only a simple majority, rather than the 60 percent needed for bonds, school levies and the like. From 1993 through 2001, according to Noble, there were no more than a half-dozen lid lifts on King County ballots. This year, there were 13, and 11 of them passed. As time goes by, Guppy said, the 1 percent limit will become a tighter and tighter bind on districts' budgets. Since inflation is almost always more than 1 percent, he said, the cap will result in real (that is, inflation-adjusted) tax cuts. With little maneuvering room to raise property taxes, he said, local elected officials will be forced to make government more efficient, attract new development to their communities, and ask voters more frequently for special-purpose tax increases. "It's very difficult to go to the voters for a general tax increase — people want to know what it's for," he said. "The best thing to come out of (I-747) is it will make government more responsive and accountable to the people." |

The

center also looked at 22 of the state's largest cities: 13 increased

regular levies by 1 percent, and six held them steady. Only Seattle,

Renton and Federal Way exceeded 1 percent.

The

center also looked at 22 of the state's largest cities: 13 increased

regular levies by 1 percent, and six held them steady. Only Seattle,

Renton and Federal Way exceeded 1 percent.